A Black Artist's Path: Book Three

An Introduction to the Journey of the Black Madonna

PDF HERE:

Book Three: The Black Madonna’s Journey Vol. I

“Black female bodies are black madonnas.”

- bell hooks

DEDICATION

To the love of my life, to my father, and to the amazing learning community I have created:

THANK YOU.

Hey Black Child,

Do you know who you are?

Who you really are?

Do you know you can be

What you want to be?

If you try to be what you can be.

Hey Black Child,

Do you know where you’re going?

Where you’re really going?

Do you know you can learn

What you want to learn?

If you try to learn

What you can learn?

Hey Black Child,

Do you know you are strong?

I mean really strong?

Do you know you can do

What you want to do?

If you try to do

What you can do?

Hey Black Child,

Be what you can be

Learn what you must learn

Do what you can do

And tomorrow your nation will be what you want it to be.

"HEY BLACK CHILD" by Useni Eugene Perkins

Pretty women wonder where my secret lies.

I’m not cute or built to suit a fashion model’s size

But when I start to tell them,

They think I’m telling lies.

I say,

It’s in the reach of my arms,

The span of my hips,

The stride of my step,

The curl of my lips.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

I walk into a room

Just as cool as you please,

And to a man,

The fellows stand or

Fall down on their knees.

Then they swarm around me,

A hive of honey bees.

I say,

It’s the fire in my eyes,

And the flash of my teeth,

The swing in my waist,

And the joy in my feet.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

Men themselves have wondered

What they see in me.

They try so much

But they can’t touch

My inner mystery.

When I try to show them,

They say they still can’t see.

I say,

It’s in the arch of my back,

The sun of my smile,

The ride of my breasts,

The grace of my style.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

Now you understand

Just why my head’s not bowed.

I don’t shout or jump about

Or have to talk real loud.

When you see me passing,

It ought to make you proud.

I say,

It’s in the click of my heels,

The bend of my hair,

the palm of my hand,

The need for my care.

’Cause I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

“Phenomenal Woman” by Maya Angelou

I believe in living.

I believe in the spectrum

of Beta days and Gamma people.

I believe in sunshine.

In windmills and waterfalls,

tricycles and rocking chairs.

And i believe that seeds grow into sprouts.

And sprouts grow into trees.

I believe in the magic of the hands.

And in the wisdom of the eyes.

I believe in rain and tears.

And in the blood of infinity.

I believe in life.

And i have seen the death parade

march through the torso of the earth,

sculpting mud bodies in its path.

I have seen the destruction of the daylight,

and seen bloodthirsty maggots

prayed to and saluted.

I have seen the kind become the blind

and the blind become the bind

in one easy lesson.

I have walked on cut glass.

I have eaten crow and blunder bread

and breathed the stench of indifference.

I have been locked by the lawless.

Handcuffed by the haters.

Gagged by the greedy.

And, if i know any thing at all,

it’s that a wall is just a wall

and nothing more at all.

It can be broken down.

I believe in living.

I believe in birth.

I believe in the sweat of love

and in the fire of truth.

And i believe that a lost ship,

steered by tired, seasick sailors,

can still be guided home

to port.

“Affirmation” by Assata Shakur

FOREWORD

The following book is about to make an argument that the source of that divine creative power is from an ancestor with some capability rooted in a Black femme/Dionysian syncretism. It is never my intention to offend anyone. Try your best to connect it to your life and the way you may create, whether or not you prescribe to any particular faith.

Summary

The world runs on the hard labor of femmes of culture and those who dare to seek the Dionysian. This week, and for the next few books, things might get emotional. If they do, it’s a good sign. It reveals how we hold ourselves back, afraid of internalizing or conjuring alternative narratives imposed upon us anyway. The activities, readings, and tasks in the next few books are based on the struggles and, most importantly, the triumphs of the Black Madonna, following the unknown, uncovering our deepest values with an open mind and heart, and redefining a different “Hero’s Journey” from our Colonial peers.

Questions to consider:

What are Thee Divine connections made in my art?

Who is my target audience?

What makes helps me stay confident in my craft?

Am I being patient enough with this process? What is there time to research or explore deeper?

What do I stand for? What am I fighting for? Who am I fighting for?

How has my creative enrichment been non-linear?

Recommended tools:

A comfy place to land for this book’s exercises.

Pen and paper (optional)

Art supplies (optional)

Introduction

In Kimberlé Crenshaw’s TED talk on the “urgency of intersectionality”, she asks her audience to stand up, if able. If someone has heard of and knows about the names that she would mention, they were to stay standing. If they did not, they were to sit down. Crenshaw first brings up the names of Black men killed by the police. Most of the audience stays standing. When she begins to mention the Black women killed by police, most people sit down. Four remain standing.

We know that being a Black artist puts one in a nuanced position where they must create dangerously. The more nuanced our position is, and the more nuanced it becomes, the more dangerous it will be. Your legacy as an artist is unique. It is not my legacy, it is not your role model’s legacy, it is not your ancestor’s legacy (altogether)–it’s yours for the taking.

One

“Black female bodies are black madonnas.”

bell hooks

It’s February, shortly after the worst of the Los Angeles fires, and it is my second time interviewing the Black Arts legend Mark Greenfield. Due to my technical failures as the daughter of a baby boomer who taught me to do everything by hand and fewer things using technology, Mark has given me the privilege of his time for an interview. He informs me that a great friend of my father and his, Alonzo Davis, founder of the Brockman Gallery, has died. My heart sank. Although Alonzo lived a long, remarkable life, it is a reminder that, in Greenfield’s words, we are experiencing a “changing of the guard” in the Black Arts Movement. “[W]e were sitting up there taking stock of it the other day,” Greenfield says, “It's like I've now–I guess–kind of joined the senior group of American artists in Los Angeles. I don't know if I wanted that distinction.” It happens to us all, he surrenders. I tell him I think it's great. “You made it,” I relay joyfully, “I think to be black and old is an achievement.”

Things do not always go as we expect them to. As an author, this very series, to me is incredibly unexpected in some wonderful and very frustrating ways. Just like bringing new life into this world, your creates its own journey. Once this journey is established, it brings growth in miraculous, organic, and elastic ways. Some days you recognize it. Other days it seems alien, and you may wonder if you even created this whole thing all by yourself. It’s hard to take responsibility for these new lives we create without identifying with them. As you may notice, the last edition of A Black Artist’s Path was released many months ago. Thank you for your patience with me. Let us now descend our project into a very massive subtopic to spread over the next three editions. I found along my research that one book alone could not say enough. Without further ado, welcome to The Journey of the Black Madonna.

Joseph Campbell is famous for his four-act story structure The Hero's Journey. It usually goes something like this: a hero accepts a call from the ordinary world to adventure. After doing all they can to refuse that call, meet with the mentor, uncover the tests, allies, and enemies that go along with the path they have chosen, experience an ordeal which they can never come back from, that may prompt their return–so they take the road back upon which they do return, and a resurrection (perhaps) brings a return with the mysterious ‘elixir’. You’ll find countless versions of this classic colonial story arc everywhere—from Homer’s Odyssey to most Star Wars films. Even though it’s one of the most popular storytelling frameworks in today’s media, I want to try something different: a non-linear, less colonial, more realistic approach.

In Art on My Mind, bell hooks defines art as “a habit of the intellect, developed with practice over time, that empowers the artist to make the work right and protects [them] ... from deviating from what is good for the work. It unites what [they are] with what [their] material is.” For diasporic artists of culture–Thee Artist–the core of our work is created with almost near certainty that we will not be compensated, discussed, critiqued, fairly–nor even celebrated in our lifetime. Knowing this, the work made with each of our particular gifts (whatever the medium may be), is rooted in what Sylvia Ardyn Boone refers to as the “...metaphysical: an informed intellect, a widened vision, a deepened discernment.” The very core of the stigma Black artists receive is based on whether or not we value our work too much (or not enough), which eventually allows that value to be questioned by the person who matters most–ourselves (Thee Artist). “All too often,” Boone says, “the uninitiated see nothing.”

In my discussion with Mark Greenfield, I mentioned a friend of mine, a poet named Denise Miller, for whom I had just created a custom oracle deck. Mark makes a funny face. He says, “Really. … That's interesting. I used to have a tarot deck”, he says, “And… then I saw some stuff I didn't want to see and I put it away.” This type of stigma is not uncommon. Tarot reading was passed down to me by my mother, who received similar comments. These small rectangles of inspiration have provided folx of many backgrounds with supplementary income, free advice, and mental health consultation, all in the palm of their hands. Albeit, it does not replace a therapist, for many communities throughout history, it may be all they have. This ancestral practice, passed down from the many ancestors in family and craft seemed to travel nations and generations to choose its reader. Who wouldn’t accept the call?

“You get chosen,” I inform Mark–quickly getting sidetracked: “I think that they choose certain people, (...) and it depends on the deck, too. I like to make my own decks, and I did a whole art series that's all of the major arcana [based on the art of] of Pamela Coleman Smith.”

I’ve never given a bad reading, and that’s not just a selling point. There are thousands of ways to interpret each one of these seventy-eight cards, 22 major, and fifty-six minor. They were designed like most art is, for interpretation. A pessimistic reader can twist every card into a warning; an optimistic one can spin each into a blessing. But a truthful reader—one with honed intuition—will tell a client precisely what they need to hear, exactly when they need to hear it. Whether the client heeds the reader’s message is their choice. I apologize to my fellow readers for exposing our magician’s trick, but Thee Black Madonna who illustrated these cards designed them to work exactly this way. Pamela Coleman Smith (1878–1951) was a Black, femme, British, artist, illustrator, and writer, best known for her work in creating the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot deck, is the most widely used deck in the entire world. This deck is often referred to as the “Rider-Waite” deck, effectively erasing the Black woman who designed them to look so iconic. Commissioned by Arthur Edward Waite, a white poet and esotericist, Smith illustrated the 78-card deck in 1909, infusing it with subjugated knowledge, and symbolism, combining imagery from different civilizations and creating the modern tarot movement as we know it. All modern decks derive in some way from her designs.

Beyond tarot, Smith was a Renaissance creative and first-wave feminist. Alongside the Lyceum Theatre and the arts and crafts movement, she worked with and in the same crowds as William Butler Yeats and Bram Stoker. Unfortunately, her story ends the same way as many incredible creative Black women’s stories: despite her significant contributions, Smith struggled financially and received little recognition during her lifetime or thereafter. Some tarot enthusiasts still take a niche interest in erasing or minimizing her contributions, if not her identity in and of itself.

One of the reasons that The Artist's Way did not work for me was how reliant the entire program was on some sort of Abrahamic religion. Evangelizing a particular religion has never been the starting or stopping point for most art, but it always results in a cult following or a gimmick that draws attention to the work.

Let’s explore this phenomenon. Artemisia Gentileschi weaponized religious narratives to reclaim her power in a time that brutalized women. Her painting Judith Slaying Holofernes wasn’t the biblical scene she purported it to be—it was a personal revenge fantasy played out on canvas in the wake of her rape by Agostino Tassi, her tutor. During the trial, she was tortured to "verify" her testimony, but not Tassi, who went on without quantifiable punishment. Her rage was her fuel. Unlike male artists who depicted Judith as delicate or hesitant, Artemisia’s Judith is a depiction that could only be accounted for by a scorned woman with sleeves rolled up as she and her maid saw through Holofernes’ neck. Gentileschi’s painting was a direct echo of the justice she was denied. The Church expected pious devotion from women, who were not often allowed the freedom to paint as men did. Artemisia gave them bloodied sheets and gritted teeth, turning scripture into a courtroom for the silenced, hijacking what the men held sacred to expose the truth of femme survival.

Fast forward to the 1980’s and 1990’s. After reading Art on My Mind, I have been particularly inspired by Andres Serrano’s work involving blood, semen, and other bodily fluids. The church has harshly scrutinized this work. Specifically, his gorgeous photo entitled Immersion (Piss Christ) in 1987 has been the subject of mass criticism. Members of the clergy both embrace and bash the work for depicting Christ on the cross immersed in urine. To many others, myself included, the work speaks to the greater connection that Serrano made on politicizing the mere existence of vulnerable people. Piss Christ says that if people exist, and if somehow a Christian “God” made everything, disagreeing with someone's existence is inherently blasphemous. If a “God” made everything on this planet and in nature, then urine is also something they created for the betterment of human bodies. For folx suffering from HIV and AIDs, debilitating sickness was dogpiled with stigma and hatred from those following certain Abrahamic religions and using them as a scapegoat to fuel their own God complex. To them, the only acceptable reason for their obstacles and oppression could be punishment from their creator. If they were true believers, however, they might know even the most unholy concepts could be brought upon by their concept of the “creator”. To put it in terms of The Hero’s Journey, this could be the “tests” stage, and we may be failing. Like all things in the world, and like my partner loves to say, “the change is never zero.”

We all get the call to adventure at one point or the other.

Religion is also a fabulous resource that can provide loads of opportunities. Mark Greenfield tells me he was an altar boy:

“I went to Catholic grade school and went to one year of an all-boys Catholic school. And I told my mother, I said, “This all-boy thing is not working for me.” So I went to L.A. High, which was a very racially diverse school. I mean, we had a little bit of everybody there, but the thing that impressed me about it was they had the one art teacher that I told you about, John Riddle, and they had a pretty interesting art department that really did stress the fundamentals. And so, to draw, you learned rendering, you learned how to paint, you learned those things. So, that part of it was important.

The other part that was kind of exciting was the fact that they had something called the Harrison Fund, which was an endowment that allowed the school to do all kinds of extracurricular things. And so, going to a museum for a field trip was like nothing [you’ve ever seen]. It's like, “Yeah, we're going to go there.” When I go to these museums and I would see paintings of the Madonna and child, I was always struck by the idea that you don't really see them in any other context than this. And I said, “what if you were to see them in a different context?” And I didn't come to that realization until a few years ago. I just was thinking about it. It's like, let's flip the script on this a little bit. Let's deal with how Catholicism looks at the Black Madonna, which is one of basically an enigma of something that can't be explained, where the Catholic Church would take everything that was more or less vague and they would put it on the black Madonna as being a mystery, stuff like that.

I think I mentioned the fact that at one point they were trying to suggest that the Madonnas were Black because of the soot that was from the candles in the different churches, but it didn't hold true because the other statues that they had of the other saints did not “turn” black either. So what was that all about? They have probably upwards of 500 Black Madonnas in France alone. They have pew in Eastern Europe mostly in the Czech Republic, and then in some instances the Madonna was actually used to kind of subversively convert people to the idea of Catholicism because particularly in Brazil you'd go and you'd see these Black Madonnas. It was a ruse to make people understand that, the saints, Mary, Joseph, all those people, “They're just like you! They're Black just like you are.” So, it made it a lot more palatable for some people. In parts of Asia, you would see Madonna and child and they'd all have [oblique] eyes, stuff like that, because, again it was one of those things to make it easier for you to relate to this as a God figure.

I decided that even though I could have been cursed for it and it was somewhat irreverent to characterize the Madonna as Black, taking on the European interpretations of it by Bernini and Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci, stuff like that, and then just blackifying them in my own but in the background of the Black Madonna paintings. You'll sometimes see little vignettes of white supremacists that were being tortured in some way, treated the same way that they did African-Americans for the longest time.”

There is often an elephant in the room in terms of Black Christianity, and that’s the many ways it has been used to subjugate us into acceptance of enslavement and oppression. Enslaved Africans were forced to take part in their white enslaver’s religion, which often operates to put Black enslaved Americans in a position where their oppression under white Americans is alleged as some sort of foreordination. In this way, Greenfield uses the symbolism of the Black Madonna as a “kind of revenge fantasy”, in his words, “But the thing that I was trying to show was the contrast between (...) these people that characterize hate, and this situation of unrestrained universal love between mother and child. Which becomes the dominant factor in all of this, and consequently, being the dominant factor, it takes precedence over everything else that goes on. (...) I had a lot of fun with it. Some of my Catholic friends are still praying for me, and say they're trying to save my soul, for which I express my appreciation all the time. Thank you very much!” Greenfield acknowledges the reality that Black American faith is both syncretic and agnostic. The metaphysical, the “spirit”, the “holy ghost”, “manifestation”, an “idea”, or whatever divine inspiration we experience is both personal and universal. It is a human experience and the root of humanity within the diasporic tradition of artmaking.

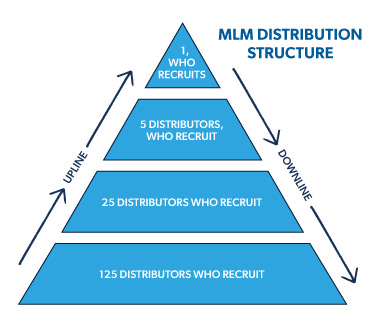

It could be argued that Abrahamic religions were the first multi-level marketing scheme. They have a point that can sometimes even bring people joy or a sense of faith, but with rapid upward mobilization and mass audiences comes disregard for the “flock”. With massive growth, most systems cannot help but move in a direction that is often exploitative of the people who make it. I believe my Abrahamic siblings are doing what feels best for them. Like many Black women whose faith lies elsewhere, sometimes I’ll even go to church. If asked, “Do you believe in God/the spirit/Christ/etc?”, I’ll agree. My spiritual identity is personal, and I don’t have to share it with anyone, but I can find it anywhere. There are forces in this world greater than humans can understand, far greater than I may even want to understand. What makes no sense to me is that hierarchies are put in place based on something so personal to establish roles and freedoms based on proximity to “creation” when we are all equal creations, and we all make creations. Good and tragic things happen to all of us. Recently, a professor of mine produced the following graphics in a Study of Love course when referring to the hierarchies placed by organized Christianity under the Roman Empire to establish colonial Abrahamic occupation, and I couldn’t help but see a connection.

These systems pose few in leadership with many followers at the bottom rung of the pyramid with little to no upward mobility. The folx at the bottom have different positions and placements, but all serve to market, establish, and maintain the positions of those at the top. Part of this marketing relies on positing those “leaders” as chosen by God, so if they start seeming exploitative and harmful, there is an easy scapegoat for their mistakes. Reliant on the argument of predetermination, life is posed as a spiritual game that places people in tragic or harmful positions because that’s just how God wanted it.

I am not a religious expert, but in my meager theosophic opinion, while acknowledging some higher mode of creation, predetermination feels incompatible with free will. It also leaves very little explanation for the things in life that seem more than just “real”. In “Freedom Dreams”, Robin Kelley refers to Suzanne Césaire as “one of surrealism’s most original theorists.” Referencing a 1941 issue of her and Aimé Césaire’s renowned WWII surrealist publication Tropiques, she refers to the surreal as “the domain of the strange, the marvelous and the fantastic, a domain scorned by people of certain inclinations. Here is the freed image, dazzling and beautiful, with a beauty that could not be more unexpected and overwhelming. Here are the poet, the painter and the artist, presiding over the metamorphoses and the inversions of the world under the sign of hallucination and madness.” Césaire was a founder of a womanist movement of organized surrealism influencing much of the work that we know and love today, like the great writer, performer, and activist Jane Cortez. Robin Kelley describes her in Freedom Dreams:

“Cortez, after all, is first and foremost an activist. In 1963, SNCC leader James Forman persuaded her to go to Mississippi, where she attended mass meetings and met with grassroots organizers, including Fannie Lou Hamer. She returned to Los Angeles that year and founded Friends of SNCC, a gathering of movement supporters that attracted a broad array of figures from the performing and visual arts. Friends of SNCC succeeded in drawing celebrities and raising money, but Cortez wanted to focus her energies on grassroots organizing. In 1964 she created Studio Watts with Jim Woods, a community theater in the heart of South Central Los Angeles’s black community that performed highly politicized street theater and poetry readings before the Watts rebellion of 1965. Studio Watts grew rapidly, attracting committed artists. Cortez and others broke with Jim Woods in 1967 and formed the Watts Repertory Theatre Company, becoming one of the most dynamic community arts projects in the nation. Although she relocated to New York soon after the WRTC was founded, she returned in 1968 and 1970 to direct Jean Genet’s moving play "The Blacks.”’

If anyone is an example of what it means to Create Dangerously, it is Jayne Cortez. In Kelley’s words, “Jayne Cortez dreams anti-imperialist dreams.” Embodying a “revolutionary commitment” to the “[B]lack radical imagination”, “[s]he wages poetic war against imperialism, racism, sexism, fascism, consumerism, and environmental injustice, while schooling those who don’t know to some of our great artists—from Nicolas Guillén to Babs Gonzalez. She creates magnetic images of convulsive beauty, to be sure, but they are fighting words. Poems such as “Stockpiling” and “War Devoted to War” reveals the connection between war and capitalism, whereas “Rape” and “If the Drum Is a Woman” are antiwar “songs” about the vicious and violent assault on women’s bodies. But Cortez is a true radical feminist; she refuses to write women as victims. One of the greatest lyrical paeans to the resistance of women to all forms of domination is Cortez’s “Sacred Trees.”

Two

As J Cole once said, “Don’t save her, she don’t wanna be saved.” Black Madonnas are not damsels in distress or victims of circumstance. We defy the odds, achieve the impossible, and create space for the immaculate. We embody the words of Sojourner Truth as she was booed and shamed by white suffragettes–the same ones we honor as valiant champions of women in our high school and college textbooks–in a women’s conference in Akron, Ohio, 1851 at a Universalist Church:

“Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all this here talking about? That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman? Then they talk about this thing in the head; what's this they call it? [member of audience whispers, "intellect"] That's it, honey. What's that got to do with women's rights or negroes' rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full? Then that little man in black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him. If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back , and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them. Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain't got nothing more to say.”

Like all good communion, Truth’s truth has sparked a conversation across generations, mediums, and contexts. The book “ain’t i a woman?: black women and feminism” by bell hooks, advocates for the glamorization of Sojourner Truth in new media while the harsh reality of Truth’s time was that she was incredibly unliked. She was written off as a “complainer”, treated by white suffragettes (women who placated themselves as leaders for “all women”) as less than what they considered woman due to her ontological and social location. That conversation was continues in the works of Patricia Hill Collin’s (Black Sexual Politics), Ntozake Shange (For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf), The works of Kara Walker (Narratives of a Negress), many many others, including this very workbook in the palm of your hand or on your screen.

The common thread that keeps this call and response alive is the Journey of the Black Madonna. This journey is non-linear, some steps repeat themselves a multitude of times, and all parts are intrinsic states of what some theorists may call maya–a proficient creator, and the many intangible things that make life what it is.

You are a proficient creator. You will mess up. You will make mistakes. You will lose people. You will also gain people that you were meant to be with because of the many people you were supposed to lose. You will gain opportunities you need to gain by failing at some point. Where there seems a door, there is sometimes a hallway taking you on a safe detour to avoid some dumpster fire out where you are meant to be. On the ulterior, sometimes the dumpster fire is only for you, and it holds the parable only you need to become a great artist.

Listen to yourself. Use these steps when things are not clear when moments seem unclear, unfair, unjustified, and impossible. Use them especially when you have unlocked a level of success you once did not feel was possible, and when you don’t know what direction to go towards, or when you don’t know what to do next. On your path as Thee Artist, go forth into the mystery and uncertainty, and if something feels unfamiliar, refer to them in non-chronological order to see where you might be:

The Black Madonna’s Journey

By Maya James

The Black Madonna is presumed innocent at all stages of their journey or quest.

The Black Madonna grows up too soon.

The Black Madonna is dislocated.

The Black Madonna believes in the promised land.

The Black Madonna is betrayed.

The Black Madonna embodies and/or illuminates a double-bind, paradox, crossroads and/or transgression, something intangible to the ordinary world.

The Black Madonna knows sorrow.

The Black Madonna knows anger.

The Black Madonna knows pain is inevitable, but suffering is a choice.

The Black Madonna is stereotyped, stigmatized, and shamed.

The Black Madonna meets or embodies an animal companion.

The Black Madonna knows no shame, for they are loved by the ancestors.

The Black Madonna is conquested, exploited. Forces attempt to make them accept a submissive role in the ordinary world.

The Black Madonna embraces color.

The Black Madonna gains Ojú Orun (heavenly ways of seeing/“heavenly eyes”).

The Black Madonna cares for themselves.

The Black Madonna is beautiful in a way that defies the binary and/or beauty standards.

The Black Madonna self-emancipates.

The Black Madonna embraces their light, the gift.

The Black Madonna embraces their art.

The Black Madonna becomes prodigal.

The Black Madonna makes a sacrifice in exchange for humanity’s progression.

The Black Madonna embraces lack with love.

The Black Madonna comes to a truce (with oneself, one’s world, one’s community, etc.)

The Black Madonna undergoes transformation.

The Black Madonna embraces the earth, in all of its terranean and subterranean elements.

The Black Madonna conjures counter-hegemony.

The Black Madonna debunks a virtue argument.

The Black Madonna accepts her mortality.

The Black Madonna accepts their abundance and connection to divinity.

The Black Madonna communicates and collaborates.

The Black Madonna learns from the example of unpleasant experience.

The Black Madonna embraces abundance with love.

The Black Madonna builds relationships with objects and the material.

The Black Madonna gains the love of creation in this world, embodying a proverb commonly known, (found in Song of Solomon 1:5) “I am black, and I am beautiful.”

The Black Madonna feasts, experiences the Dionysian, embraces pleasure where it can be found and made.

Forces attempt to erase the Black Madonna from existence and history.

The Black Madonna finds comfort in the night.

The Black Madonna knows joy.

The Black Madonna fights to the death.

The Black Madonna is celebrated.

Part of this journey may sound familiar. Each of these steps will be expanded upon in books to come. The Black Madonna is presumed innocent at all stages of their journey or quest, as we know the stigmas against Black femmes lead them to be vilified from birth as nefarious. When we presume Black femmes as innocent, we create positive change for all individuals. The Black Madonna grows up too soon, due to the apparatus of adultifying Black femmes before they have a chance to understand their own identity (as early as five years old), and this drives the necessity for artistic expression across mediums at a young age. The Black Madonna is Dislocated due to ontology and the many mass Exodus that have established a culture of diasporic artmaking in exile. The Black Madonna believes in the promised land, so the purpose of these Exodus and Great Migrations turns into an organized magical surrealist standpoint, establishing the importance of accepting context and nuance in our communities as well as in the world at large. The Black Madonna is betrayed. We know this. In this portion of A Black Artist’s Path, we investigate the many ways that the Black Madonnas of the art movements are betrayed for the extraction of their inherent creative abundance. The Black Madonna embodies and/or illuminates a double-bind, paradox, crossroads, and/or transgression, something intangible to the ordinary world, establishing nuance to better our creative ecosystems and personal practices. The Black Madonna Knows Sorrow, core of why we create. Loss and grief can create a renaissance within and without. The Black Madonna knows anger and anger can be a positive, constructive emotion when used wisely. When we curtail it, embracing it from a place of nonviolence, we can allow that part of ourselves to inform us of what we need to create more sustainably and in community with others, because The Black Madonna knows pain is inevitable, but suffering is a choice–and ultimately the extenuating of our pain with anger in the form of violence or harm towards others–in any capacity–elongates our suffering and becomes an obstacle between us and our creativity. The Black Madonna is stereotyped, stigmatized, and shamed. Dogpiling on our Black Madonnas is an ever-present painful reality, and letting the collective distract us from our creative capacities is an elongation of that pain, which is why sometimes The Black Madonna meets or embodies an animal companion, whether it is a fierce alter ego that can fight on our behalf or a real companion who guides us towards our highest good and most intentional life.

Since this path is non-linear and non-chronological, we may find little pieces of proof that The Black Madonna knows no shame, for they are loved by the ancestors. There are angels in the details–whether a line of a poem that seems like the next step forward, to a reference book from a project that may or may not work out, featuring an artist residency that takes you forward in your career. It could also be a picture from an artist hundreds of years ago that looks just like you. Wherever your ancestors lie, listen to them. The Black Madonna is conquested and exploited. Forces attempt to make them accept a submissive role in the ordinary world. Surreal messages we find in the details often keep us out of harm’s way. Ontology allows us a deeper understanding of color, so naturally, The Black Madonna embraces color. In color, The Black Madonna gains Ojú Orun (heavenly ways of seeing/“heavenly eyes”). Imagination leads us to create masterpieces and works of art that have legacies far after we are gone–so while we are here, The Black Madonna must care for themselves, because the folx that enjoy our work will probably want more than just one or two pieces of masterful creations to chew on–and sometimes these creations take decades.

Legacies have established that The Black Madonna is beautiful in a way that defies the binary and/or beauty standards. Beauty and potential can pass through generations and spark meaningful dialogues across communities. Through the work, we create new movements and potentials that only Thee Artist can establish, which is why The Black Madonna self-emancipates, freeing themselves if only for a moment, because The Black Madonna embraces their light, the gift overcoming the burden of the emotional labor that others’ perceptions. The Black Madonna embraces their art once they find a flow in their creative process. It is at that moment that The Black Madonna becomes prodigal, searching for the tradition that led them to where they are and the different forms, techniques, and mediums that their ancestors created. The Black Madonna often makes a sacrifice in exchange for humanity’s progression, choosing to lose one or many things to bring the rest of the world into the future. The Black Madonna embraces a lack with love due to the many sacrifices they make because often The Black Madonna must come to a truce (with oneself, one’s world, one’s community, etc.). The Black Madonna transforms once they come to that truce, working towards their good and fulfillment. The Black Madonna embraces the earth, in all of its terranean and subterranean elements, once they find this purpose, leading inevitably to The Black Madonna conjuring counter-hegemony. When alchemizing this counter-hegemony, The Black Madonna debunks a virtue argument. The Black Madonna accepts her mortality recognizing that their life may not be about being some protagonist or antagonist in a story centering the world around them, which makes the moments so much more valuable. With the discovery of this newfound and simultaneously inherent value in the presence and persistence of life, The Black Madonna accepts their abundance and connection to divinity. Understanding that we all might come from the same star stuff, The Black Madonna communicates and collaborates with their peers, because to love is a risk, but it always makes us better in the end. The Black Madonna learns from the example of unpleasant experience and knows that there are going to be some dark, awkward, and just uncomfortable times, so The Black Madonna embraces abundance with love, appreciating what they have while they have it. The Black Madonna builds relationships with objects and the material because people and sometimes even animals disappoint us.

Additionally, material things represent a symbol of freedom that cannot be attained by mortal beings. The Black Madonna gains the love of creation in this world, embodying a proverb commonly known (found in Song of Solomon 1:5), “I am black, and I am beautiful.” The Black Madonna feasts and experiences the Dionysian and embraces pleasure where it can be found and made, which attracts jealous onlookers and snakes in the grass who may feel unfulfilled in their creative practice. These Forces may go so far as to attempt to erase the Black Madonna from existence and history. They may go into hiding. That’s why The Black Madonna always finds comfort in the night. Even on the darkest night, they can find joy. The Black Madonna knows joy. Because this joy is so intoxicating, The Black Madonna fights to the death, because they know that everyone deserves that joy. At some point, The Black Madonna is celebrated, but probably not within their lifetime, so they come to terms with reality and celebrate themselves.

The Black Madonna stands by themselves, their own best advocate. While artists often celebrate nuance and difference, when we know who we are–warts and all–we can stand beside that person. In Freedom Dreams, Robin Kelley says that the work of Jayne Cortez is a “warning to the liberals and fence-sitters who don’t believe that we are fighting for our lives”. It truly is incredible to see some of the most heinous and evil authoritarian politicians in history sleep at night with ease, relaxation, confidence, and self-esteem while I watch well-intentioned and progressive artists and activists micromanage, criticize, and judge their peers’ and their own every move with abandon. It amazes me how little we allow ourselves and each other to make mistakes. Instead of tough conversations, we spark dialogue from a position of blame and shaming.

It could be argued that stigma against Black femmes for being “mysterious” originates alongside a spiritual, motherly divine figure that may even represent a creator herself/themselves. During the Journey of The Black Madonna, we will explore the many instances where the Vatican and other Abrahamic religious organizations have blatantly whitewashed depictions of her symbolism across faiths and cultures, and how her Black femme identity is erased. In my conversation with Greenfield, I tell him, “I think that in terms of the Black Madonna, if the Black Madonna wasn't an actual African woman or a woman of African culture, why is there a stereotype of African women being mysterious? (...) It's like, wait, there's this huge stereotype and it's negative and positive, (...), even when we're exoticized or fetishized, that we're mysterious. “You never know what she's doing! She's a witch!” [they say]. … and I think that connects deeply to the work that you do about the Black Madonna.”

“That's why I need people like you to interpret what it is that I'm doing,” says Greenfield.

“Yeah.” I reply, “I feel like it's very Divine.”

Speaking to Greenfield feels like speaking to a lost relative, perhaps an uncle, definitely a play uncle. There’s something magical about seeing an artist who you can relate to alive and well into old age. For a moment, there is a future.

Throughout history, there have been many depictions of a seemingly mysterious woman or femme person of dark or olive complexion, often holding her child or accompanied by animals. The Black Madonna has made her mark on the arts, she has many names–The Virgin Mary, Isis, Artemis, Kali, Santa Maria Del Popolo, the Virgin of Regla, Yemaya, Cybele, The Cosmos, Mother Earth, even Dionysus. Sometimes, she defies mortal norms of gender and hierarchy. She establishes justice, and she grants faith in life. She is often othered, treated as some type of foreigner or “alien”. She is found in history, myth, religion, astronomy, astrology, fable, and parable. She creates or exists in altars that should be untouched but are often desecrated to rewrite history. She represents the cosmos, the earth, fertility, death, and all the things that make life what it is: nurturing, purification, transformation, regeneration, protection, justice, and pleasure.

Most of all, she is the lifeblood of creativity. Anyone can embody the Black Madonna; all it takes is faith in the imagination. My favorite Abrahamic vision of the Black Madonna is in Larry Scully’s Madonna and Child of Soweto, a painting he created in 1973 that lives at the Regina Mundi Church in Soweto, South Africa, visited and venerated as a Holy creation by people from all over the world. Like Greenfield, Scully is another often-overlooked artist. Larry Scully, or Laurence Vincent Scully, was born to an Irish father and South African mother in Gibraltar on December 12, 1922. He lived until 2002, and in the interim created stunning abstract expressions. Scully himself experienced the Journey of the Black Madonna. According to his artist statement:

Scully spent most of his youth in Portsmouth, England. The family was very poor and he left school and home at about 13 years of age to go to work in a grocery shop in order to help to support his family. When he was 15, the family moved to South Africa. From 1939 through 1946, Scully served in the South African Permanent Forces working as a draftsman. In that time, he also obtained his high school degree through correspondence courses. This qualified him to obtain a grant to study at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in Johannesburg, from 1947 through 1950. There he was part of a cohort that included Cecil Skotnes, who remained a kind friend throughout Scully's life, and Christo Coetzee, Helen Anne Petrie and Esme Berman. In 1963, he became the first person in South Africa to be awarded a Master of Fine Arts degree (cum laude).

In the late 1940s, Scully taught at the Polly Street Art Centre in Johannesburg, one of the first art schools on the continent designed to encourage African artists. Polly Street asked him to become director, but Scully reluctantly declined because he needed to pay off his student loans. He became certified as a teacher and from 1951 through `65 taught Art at Pretoria Boys' High School, where he followed in the footsteps of his mentor Walter Battiss. In 1959, Scully married Christine Frost, pianist and teacher at Pretoria Girls' High. They had twin girls in 1962 just before the family moved to Johannesburg.

The late 1950s and 1960s saw Scully defining his style. An excellent still-life artist and landscape painter, Scully also searched for new forms, experimenting with shapes and textures inspired by African masks, but finally finding in abstract art a passion that remained with him always. His artistic career really took off in 1962 with his one-man exhibition in Pretoria at the South African Association of Arts (SAAA) gallery. He had many exhibitions over the next few years, and won the prestigious Oppenheimer Painting Prize in 1965. In 1966, he represented South Africa at the Venice Biennale, and again at the Sao Paulo Biennale in Brazil in 1967 (with 8 paintings). In the course of the 1960s and '70s, he held numerous one-man exhibitions at galleries such as The Goodman Gallery, the Botswana National Gallery, and at SAAA galleries throughout South Africa.

Scully, who was 6 ft 8 inches tall, also painted on a large scale. Among his most famous works are two murals, one in the Dudley Heights building in Johannesburg, entitled Cityscape, and the other for the Conservatorium of Music at the University of Stellenbosch. He called the Dudley Heights murals, painted in 1971, "environmental murals" in part because they attempted to render the vista of a city connected to the golden mine dumps that circled it. The University of Stellenbosch commissioned him to paint his Music Murals in 1978. A series of large paintings and smaller works fill the entrance foyer. Scully modeled the murals on the mandala concept of peace and balance. He saw these murals also as an "African symphony" and homage's "to Bach, Satie and Debussy."

Scully held various leadership positions within the art world, both in education and in civic life. He was head of Fine Arts at the Johannesburg College of Education from 1966 to 1973, when he decided to resign in order to paint full time. In 1976, he became Professor of Fine Arts and Art History at the University of Stellenbosch, a position he held until 1984. He was chair of the South African Association of Arts in Johannesburg, and National Vice-president from 1969-1974. He also served as Chairman of the Venice Biennale selection board in 1970 and was a member of the Aesthetics Committee of the Johannesburg City Council from 1970-1974. He was a Trustee of the South African National Gallery from 1978 through 1984.

In the 1970s, Scully headed a committee organizing a Johannesburg Biennale. He planned to have all South Africans represented as artists and audience members. A week or so before the biennale was due to open, the South African government ordered Scully to limit the biennale to whites only. Scully refused to agree to this and shut down the biennale immediately. This was an unusual and highly principled action at a time when most whites supported Apartheid and did little to challenge racial discrimination.

Scully was Art Editor of The Sunday Express newspaper in Johannesburg from 1973 to 1975. In that column he highlighted the work of his peers and also used the forum as a place to display his increasing interest in black Johannesburg and the creative tensions arising between the building of skyscrapers such as the Carlton Centre, and the poverty and experiences of black South Africans working in the apartheid city. The slides he took documenting the developing city, and many others taken both in South Africa and during Scully's frequent trips to Europe and the USA, became the basis of his famous "multi-image" slide shows. He would set up 5 projectors and manually projected slides at a dizzying pace to music. Audiences often left the shows in tears of overwhelming emotion and delight. Scully never repeated a show, an impossible feat since the eleven thousand or so slides generally ended up in a jumble around him on the floor. Scully held these shows at The Baxter theatre in Cape Town, Stellenbosch Town Hall and various other venues.

In 1973, The Star newspaper, a liberal, anti-apartheid newspaper in Johannesburg commissioned Scully to paint a picture to raise money for an education fund for black South Africans. Scully painted The Madonna and Child of Soweto, some 8 foot by 5 foot in size. Harry Oppenheimer of Anglo American bought the painting and donated it to the Regina Mundi Church in Soweto. Regina Mundi was the site of much anti-apartheid activity both in the 1970s and through to the ending of apartheid in the 1990s. Numerous funerals of activists were held in the church and many organizations used the church for meetings. During the student uprising in 1976, students fled to Regina Mundi after police shot at them. In 1997, Nelson Mandela declared Regina Mundi Day in recognition of the importance of the church to the anti-apartheid struggle. As Michael Morris has noted, the painting "had a prophetic quality: the focal point is the child's right hand, forming a victory sign." [Morris Interview with Scully in Matieland February 2002]

In 2004, journalist Mpho Lukoto reflected on 10 years of democracy in South Africa by saying of the painting:

"Perhaps one of the most poignant reminders of the past is the Black Madonna and Child of Soweto, which was painted by Laurence Scully. Beneath the image of the Black Madonna, Scully painted an eye, with the different images in it giving meaning to the picture. The pupil of the eye represents the township. The two black forks that run across the eye toward the pupil represent the pain inflicted on black people. And in the centre of the eye, representing the church is a cross with a light that illuminates the pupil. It struck me that in the midst of all the painful memories, the painting is a symbol of the hope that, like the church itself, was in the heart of the people. I like to believe that it was that hope that makes it possible for us to celebrate 10 years of democracy." The Star, March 23, 2004

Today thousands of visitors still see The Madonna and Child of Soweto on tours of the City; and the image of the black Madonna is printed on t-shirts that are sold across South Africa. In the 1970s, Scully continued to document the changing landscape of Apartheid South Africa, taking numerous photographs of District Six as it was demolished to make way for white settlement in the centre of Cape Town. His photographs of District Six are housed in a permanent collection in the Stellenbosch University Art Museum and in the District Six Museum.

Scully's location in Stellenbosch seems to have drawn him away from the art world in Cape Town, and by the 1990s, Scully was increasingly being acclaimed as a son of Stellenbosch. By his death in 2002 people were rediscovering his work as a lyrical testament to the human spirit—primarily rendered through his beautiful abstract paintings such as Nkosi' Sikelele iAfrika, completed in 1997 as a celebration of the New South Africa, and through his photography. Scully was a photographer of distinction, winning the South African Republic Art Festival photography prize in 1981. In the 1980s, Scully experimented also with photo-drawings (where he drew with pen on photographs). His most celebrated works are a series Xhosa Initiates with Transistor radio. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art owns one of these photo-drawings. Scully also documented miners' decorations of their bunks in the mining compounds around Johannesburg.

Scully's works are held in various public collections including The Royal Palace of Lesotho, The South African National Gallery, Hester Rupert Museum, The Pretoria Art Museum, Jan Smuts International Airport, Pretoria Art Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Universities of the Witwatersrand, Cape Town, Stellenbosch and UWC. His paintings and photography are also in private collections around the world including in Australia, Ireland and the United States.

Scully said of his love of painting:

"Painting is for me visual music and visual thinking. My inspiration comes from the colours, textures, forms and light of Africa, and is a continuing search for unity out of diversity."

A tall, kind man, who nevertheless often infuriated people he worked with in part because of his penchant for whipping out a paintbrush in the middle of a conversation, or demanding the right to change a painting that was now in the possession of a gallery or individual, Scully was a legendary educator. He inspired devotion among many of his students long after his days as a teacher. His direction of Macbeth and Julius Caesar while a young teacher at Pretoria Boys' High School is still remembered by many pupils and members of the audience. Larry sometimes reflected that if he had been born a few decades later he might well have become a film director as well as a painter.

Scully had a wonderful capacity for striking up conversations with acquaintances he met through his love of art, tennis, music and travel; and these chance meetings often developed into fast friendships, such as his longstanding friendship with the Iranian tennis player Monsour Bahrami. Larry also corresponded with Christo, listened to music with Jacqueline Du Pre (he wrote to her when in London and said he loved her music and would like to listen to her Elgar cello concerto with her—she invited him to her home to do so) and became fast friends with pioneering art critic Tsion Avital.

While not an overt political activist, Larry Scully's desire to recognize the humanity in all people on all sides of the difficult divide that was Apartheid South Africa is probably his lasting legacy, symbolized indeed by his beloved Madonna and Child of Soweto and by his multi-media images of District Six, a passion he shared with fellow contemporary South African artist Helen Anne Petrie.

The Madonna and Child of Soweto as an anti-apartheid symbol in an anti-apartheid sanctuary proves The Black Madonna is a symbol of abolition and human progress. Regina Mundi is the largest Catholic church in South Africa, a gathering center for anti-apartheid activism during the crucial years when political meeting was banned in most public spaces. The importance of its role as a gathering place is legendary. The art statement notes that “journalist Mpho Lukoto referred to Scully’s works as poignant reminders of [South Africa’s] difficult past and enduring symbols of hope for the future (The Star, March 23, 2004).” Perhaps the most dangerous thing about the Black Madonna is that her existence can transcend mortal religious fervor as a true, universal symbol of peace, but not peace from passivity–peace that one has to fight for. Perhaps my favorite part of this depiction is the peace sign the child is sporting in his mother’s arms. Scully’s work places joy over all, especially in the face of danger in a surveillance state.

Copts, an ancient sect of North African Christians, spread what they consider to be ancient knowledge about this figure to this day. The iconography of a dark-skinned, beautiful femme figure who represents a divine creator can be found across cultures, interconnecting ancient civilizations all over the world from which we descend. In Art on My Mind, bell hooks references Michelle Wallace’s essay Why Are There No Great Black Artists?' The Problem of Visuality in African-American Culture, which argues that engaging Black art fully requires comprehension of "how regimens of visuality enforce racism, how they literally hold it in place." Echoing the sentiment of Faith Ringgold’s daughter, hooks correctly argues that the “system of white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy is not maintained solely by white folks.” Yes, Abrahamic religions were forced upon Black and brown people, but some of us brought these faiths into the future and the light without a second thought, whether for survival, community, or out of true belief, regardless of the ways it is used to subjugate vulnerable populations.

Something that gave me a distaste for following in my father’s footsteps as an artist is a phenomenon bell hooks refers to, where “individual white men who entered the art world as rebels have been canonized in such a way that their standards and aesthetic visions are used instrumentally to devalue the works of new rebels in the art world, especially artists from marginal groups.”

Three: Nobody gets famous by ‘accident’ (Fame and CIA infiltration of the arts market)

There is a myth in the creative field that must be debunked this instant. Fame is not an accident. No one is ever really “discovered”, especially in the arts. By now, it should be pretty obvious to most people that games are fixed, and the arts economy is no exception.

Let’s go back to Jean-Michel Basquiat, mentioned in previous texts, whose career served as a media circus for otherwise economically drowning marginalized individuals in New York and elsewhere. In Art on My Mind, bell hooks ponders:

“Despite the incredible energy Basquiat displayed playing the how-to-be-a-famous-artist-in-the-shortest-amount-of-time game–courting the right crowd, making connections, networking his way into high “white” art places–he chose to make his work a space where that process of commodification is critiqued, particularly as it pertains to the black body and soul. Unimpressed by white exoticization of the “Negro”, he mocks this process in works that announce an “undiscovered genius of the Mississippi delta, “forcing us to question who makes such discoveries and for what reason.”

hooks poses an important inquiry: Why do people get famous in the arts, and why is the “discovery” so important to everyone? An unfortunate reality in arts and culture today is that we have developed a collective, influenced, and established mindset on fame. It is incredibly upsetting to have grown up watching everyone buy into a unanimous and imposed mindset to yearn for fame for while those who attained it unanimously end up dreading it. hooks notes that in Basquiat’s work, “Fame, symbolized by the crown, is offered as the only possible path to subjectivity for the black male artist. To be unfamous is to be rendered invisible. Therefore, one is without choice. You can either enter the phallocentric battlefield of representation and play the game or you are doomed to exist outside of history. Basquiat wanted a place in history, and he played the game.”

We understand now why the “game” was created in the first place. Every creative young Black person with a pulse and a dream starts out wanting to play this “game”, even if that means enthusiastically accepting chauvinism, sexism, and chumming up to abusive people (or even being abusive themselves). After all, that is how it is played. What these young dreamers often do not know is that the game itself was established by our governments as well as the elite.

bell hooks quotes Braithwaite on experiencing fame:

“...you’ve waltzed your way right into the thick of it, and probably faster than anybody in history, but once you got in you were standing around wondering where you were. And then, who’s here with me?”

No one.

Tall Poppy Revisited: Megan Thee Stallion

In her recent documentary, Megan Thee Stallion: In Her Words, Megan reveals the reality of skyrocketing fame from her perspective: “I feel lonely in every relationship in my life, and there’s nothing that nobody can help.” Many celebrities have come forward to say that fame ended up a lonely, isolating, and depressing place, no matter how much success they may accrue. It begs the question: should this be something to aspire to in the first place?

Megan wakes up at one in the morning most days to get her makeup done, then performs and makes appearances well into the night. This does not include her rigorous practice and training schedule. This exhaustive routine takes a toll, and sometimes publicity, wealth, and fame don’t seem as glamorous as they once were. What was once an honest sentiment becomes a persona. What was once performing art becomes a record on repeat. “How can I be Megan Thee Stallion and I’m not even fun?” Megan asks herself, “I feel like I’m always on the verge of some breakdown.” At a certain point, no one is genuine. Every bright light attracts snakes, which makes it pretty obvious why Megan adopted the persona of a Cobra in her hit song released in 2024. The lyrics start out:

“Breaking down and I had the whole world watching

But the worst part is really who watched me?

Every night I cried, I almost died

And nobody close tried to stop me

Long as everybody getting paid, right?

Everything will be okay, right?

I'm winning, so nobody tripping

Bet if I ever fall off everybody go missing.”

The song goes on to say:

“I'm sittin' in a dark room thinking

Probably why I always end up drinking

(Yes), I'm very depressed

How can somebody so blessed wanna slit they wrist?

Shit, I'd probably bleed out some Pinot

When they find me, I'm in Valentino, …

He pouring me shots thinking it's lit

Hah, little did he know:

Megan has been fetishized and written off as a gimmick artist in the realm of rap while actively relaying to her audience the dangers of a culture based around fame as the only goal. Her documentary shares behind-the-scenes shots of her performance on Season 48 of Saturday Night Live, Episode Three. Megan enacts her hit song Anxiety. Behind the scenes, a white woman on her staff notes the tears in her eyes. “Is she crying?” she asks. “I don’t think it’s a good thing.” “I think she’s stressed”, says another white woman on her staff. Their concerned looks turn into congratulations and celebrations as soon as Megan walks into her dressing room after the performance. Everyone is telling her she did and looked amazing, giving no notes of concern for her emotional state, like the moment before.

It seems like before and after most of her performances, Thee Stallion is glued to her phone, constantly feeding her worries of public misperception with the hatred and criticism her audience dog piles onto her. Her Anxiety is not unwarranted. Two men took her performance as a perfect opportunity to break into her home and rob her of over $400,000 of her belongings. Megan says during this time “[e]verything was ugly through my eyes. (...) I’m really lonely,” she recalls, “And I didn’t feel like I was worthy. And I didn’t feel like my life had any value.”

It’s safe to assume, after being shot, having her home violated, as well as having her every move tracked, criticised, and put up for public debate, that Megan is processing a lot of trauma. This is common among successful Black Madonnas like Thee Stallion. “I don’t remember the last time I felt safe”, she says, “I don’t remember the last time I’ve been calm.” In her documentary, she stays in bed for days at a time battling suicidal ideation, with very few resources in her immediate community to support or protect her.

The strangest part is that I was right there, witnessing it up close. I had the privilege to join my friend Rashaad Lambert’s Forbes The Culture at the Forbes 30 Under 30 Summit, depicted in her documentary, and meet her. I even asked if I could paint her portrait, and she agreed. By the end of her keynote, Megan was encouraging every woman in the room to “shoot their shot”—even as her security and management tried to discourage her, to hurry them along. I’d never seen someone so committed to uplifting others, even at the cost of her own time and safety. It reminded me of another Texas legend, Selena Quintanilla-Pérez. Despite pressures and scrutiny, she went out of her way to empower ambitious, overlooked women at the conference. She promoted one woman’s book and hired another on the spot. I scribbled my info on the back of someone else’s business card and handed it to her, but I’m pretty sure she either lost it or couldn’t read it, or thought I was insane. Still, it was one of the best days of my life. Every move she made was effortlessly graceful, posing for a portrait no matter where she stood.

[insert picture of her portrait]

A year goes by. I joined my partner and Oxfam to create a mural and petition against the export of fossil fuels along the gulf coast at Bonnaroo. Megan was performing. Like many of the performances in the documentary, the crowd turned ugly. In Coffee County, Tennessee, White women shoved and elbowed in the crowd, desperate to get her attention or at least the attention of her photographers. They screamed rehearsed lyrics at her while pushing Black women toward the back.

I wonder if she ever expected this to happen at her performances at local strip clubs and parking lots back in the day. The life of Megan Thee Stallion should teach us to appreciate our come-up, because it may be the most peaceful, authentic, and wholesome time Thee Artist’s life. It is still disturbing to imagine one of the most graceful, intelligent, and confident Black femme performers out there in a state of constant fear. After her court case in Megan Thee Stallion: In Her Words, Megan insinuates residual concerns for her safety: “I still, everyday, have to deal with people mad at me because I said what happened to me” she says, “But I do feel like I’m in a place where I really don’t care. I care about my damn self.”

Fame forces its victims into a state of social isolation and obscures their perception of reality due to its enterprising forces. Megan’s cousin, one of the very few people left in her life who unconditionally love and support her, reminds us, “[s]he needs love man. Everybody need love”. The rugged individualistic persona Thee Stallion perpetuates is a stage presence, not the whole story. It is impossible to be isolated from reality and humanity and come out unscathed, even if it means great success. Her cousin also shines a light on the collateral damage from the dogpiling on Megan’s career and public skepticism of her integrity after being shot by a marginally famous Black man:

“If I was on the outside looking in and something had happened to me, I wouldn’t come forward. If this famous lady can have this happen to her and nothing gets done about it, what does that say for a person who is just a civilian who doesn’t have the resources to fight, who can’t afford a lawyer? What do that say?”

She has an important point. We must ask ourselves if a culture of fame is being used as a method to oppress vulnerable populations through osmosis. If a Black femme millionaire like Megan can be bullied into suicidal ideation, and if a Black femme billionaire like Rihanna can face harsh collective criticism for being a victim of domestic abuse and attempted murder, what does that say for the rest of us aspiring unfamous artists? Should this be the goal of creativity? If not, what should?

In 1950, the modern American art movement was born, along with the newly established CIA formed what was known as the Congress for Cultural Freedom. The program was founded and highly funded by taxpayer dollars to “propagate the virtues of Western democratic culture.” This organization allegedly operated for seventeen years with operations in thirty-five countries, employing personnel, publishing over twenty prestige magazines, holding art exhibitions and showcases, and propagating news features. One of the purposes of this organization was to establish a culture of “high art” with little participants of color or free thinking artists of vulnerable populations, blacklisting many as Marxist sympathizers. The program organized high-profile international conferences and rewarded musicians and artists with prizes and public performances that would create a foundation of hierarchy and hypocrisy in the art market, creating a deficit for the many talented people of color in the arts market forever. This practice is known today as gatekeeping. The headquarters was even placed in France, establishing a eurocentric model of high-end art that was only accessible to already well-resourced white artists. This organization explains many heavy investments in the arts by the administration of Michigan’s own Gerald Ford, whose name adorns a museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan–to the massive investment in artists like Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, and other wealthy white expressionists and pop artists that tip the scale ever more in the favor of an elitist and racist institutional majority.

In Art on My Mind, bell hooks quotes Thomas Moore in his description of fame when he says, “...the turns of fate almost always go counter to the expectation and often to the desires of the ego.” Another great way to sabotage your success on this path is to walk forth in the expectation or anticipation of fame, even if that’s where things are going to end up. Enjoy the here and now. No matter where you are in this journey, you have already done enough, you will accomplish more, and you are not a lost cause. Fame is mostly desirable to those who don’t have it, and it seems to be more unpleasant for those who do. Let me offer, instead, your own unique journey, in all of its setbacks and milestones, as a complete and whole legacy, regardless of who is seeing it and how it is perceived. The culture of fame is an illusion created to distract you from your true purpose in progress.

For many Black femme or Dionysian artists, fame is never a possibility. This is especially true for Black Trans/Femme artists. Most of our legacies are erased between the lines of “Black” and “woman”, two worlds that resist uttering in the same sentence. bell hooks herself used a pseudonym to protect her rights from infringement, however possible. In Art on My Mind, hooks mentions Cornel West’s misstep in the acknowledgement that a “decisive push of postmodern black intellectuals toward a new cultural politics of difference has been made by the powerful critiques and constructive explorations of black diaspora women,” without naming said women at all. “The work of black female critics informs this essay,” laments hooks, “yet our names go unmentioned.” This path will say their names, adorned with the flowers of our creative predecessors and descendants alike. For Black femmes like Thee Stallion, hooks, Jayne Cortez, Suzanne Césaire, and the many who are unmentioned even in this book, our pursuit of peace, love, testimony, and humanism lies in the creative embodiment of our specific lived experiences.

And, if only for that, won’t you celebrate with me?

Exercise #1: Testimony

This exercise is entitled “Testimony”. It takes an hour to an hour and a half, and can be done alone or with a group. Make sure everyone participating is in a comfortable place with access to water, cushions, blankets, and the art medium of their choice if they would like to express testimony with creative practice. Follow along the steps of the journey, either reading the stages out loud or reading them silently to yourself. You can listen to our recording of the journey or record yourself reading the steps and follow along that way. It is also nice to accompany with some light ambient noise, or any music that does not have lyrics or singing. If you feel so inclined, check out my curated special ambience playlist with 350+ moods and virtual environments to bring you to a calm, centered, and inquisitive space (https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLiYdLWReGvTOAlX5nReZEIYSCLemjgRhh). You can do this exercise actively (awake, aware, making art or sketching during each step) or passively (in a meditative space). There are no wrong ways to be during this experience, as long as you stay engaged and inspired. One word, meditative vocal shout-outs are welcome at a neutral tone, try not to shout, even if you are asserting your voice. Do your best to keep it to one word so that you can visualize. You don’t have to share out and, alternatively, don’t be afraid to get too loud, as it is just some creative spirit or energy carrying you. If you hear something that resonates with you, snap your fingers or quietly raise your open hand or fist, or bow your head in testimony. Try to separate this meditation from the author, or it will not result in the actual work you need to do. This is introspective work, and it is yours alone.

The Black Madonna is presumed innocent at all stages of their journey or quest.

If it feels right, drop your shoulders down your back, relax your tongue from the roof of your mouth. Close your eyes. Imagine the warmth of sunlight on your skin, the softness of your breath as you relax. Can you hear the sound of your heartbeat in your chest? Feel the ground beneath you—solid, steady. The air around you—warm, cool, or fragrant. Notice the sensation of your body becoming lighter, more relaxed. Imagine you are where you grew up. Who’s all there with you? How old are you? I invite you to imagine yourself as a ball of light. Notice the flaming atoms in this ball. Now expand it bigger and bigger until it makes the shape of who you were as a child. Picture your inner child holding that ball of light in your heart. Try to remember a time when you were innocent, curious, just discovering everything around you.

The Black Madonna grows up too soon.

Imagine the rate at which your body grew into an adult, now go back to that child-like experience. Now try to examine at which rate your mind had to grow into an adult. When you do, go back to that inner child. Now, imagine the rate at which your heart had to grow up.

The Black Madonna embodies and/or illuminates a double-bind, paradox, crossroads, and/or transgression, something intangible to the ordinary world.

Try to find your child again. That beautiful, innocent young chil, –full of light. Now remember that moment that that “child” found out the thing that would separate themself from everyone else in the world. If you know it, you can even take this time to write it out on your preferred medium.

The Black Madonna believes in the promised land.

Imagine the big dreams you had then. What did you want to be when you grew up? Why? In what ways have you become that person? In what ways was that person a fantasy?The Black Madonna is betrayed.

Imagine the moment in your life when those big dreams became harder to envision. What changed about who you wanted to be? What changed about the world around you?

The Black Madonna embodies and/or illuminates a double-bind, paradox, crossroads and/or transgression, something intangible to the ordinary world.

Did that world create negative assumptions? What were they? Can you think of a time when those negative assumptions were wrong? What did you learn from that?

The Black Madonna knows sorrow.

Challenge yourself to remember a time that this differentiation from others caused you sorrow. What does the weight of that moment feel like physically?

The Black Madonna knows anger.

Can you make room for the pain, frustration, or rage that might come out of that moment?

The Black Madonna knows pain is inevitable, but suffering is a choice.

If you don’t make room for the anger, it stays with you. Has there been a time when the pain, frustration, and rage made it a lot harder than it had to be? All answers are acceptable.

The Black Madonna is stereotyped, stigmatized, and shamed.

Has that pain shown up in an unwanted space before? Did it create assumptions, or reactions to assumptions?

The Black Madonna meets or embodies an animal companion.

Now imagine yourself as an animal, or running alongside an animal. The animal is non-violent. It truly does have your best interest at heart. Imagine where you are, imagine your animal nature.

The Black Madonna knows no shame, for they are loved by the ancestors.

Do assumptions even matter? Does anyone’s opinion ever matter except your own?

The Black Madonna is conquested, exploited. Forces attempt to make them accept a submissive role in the ordinary world.

When was the time that sorrow made you behave smaller than you really are? Feel free to embrace that area or just pay attention to that area for a while. Imagine what that area looks like. Where does the sorrow linger in your body? Can you release that part of yourself just a little bit more to ease that space?

The Black Madonna embraces color.

What color does that part of your body look or feel like? What is the color of that sorrow? Is it dark and muted, or does it feel sharp and vivid? Now, bring in your favorite color. Can you feel the joy it brings? Is it warm and soothing, or something else? When you imagine these two colors together, does one overpower the other, or do they blend harmoniously? What does the contrast taste like? Is it bitter? Sweet? Just right? Do you like the pair? Why or why not?

The Black Madonna gains Ojú Orun (heavenly ways of seeing/“heavenly eyes”).